Due to a recent influx of information concerning the progress of the anthropocene, and its intersection with the continuing spiral of the health food and diet industries through the world market, it is easy to see concerns relating to immortality, sustainability, and livelihood that all contribute to notable changes in dietary behaviors as well as economic practices.

How humans have attempted to find their own bodily immortality (or something close to it) by means of what they eat, as has been studied by many, including but definitely not limited to Alexander the Great, Henry Ford, and John Locke. Obviously, the obsessions also carry to the rest of us through Buzzfeed articles, detox diet plans, and Soylent packets, and have different values concerning sustainability of nourishment in our particular environments.

Henry Ford (R) holding patch of wheat and standing with son Henry Ford II (2L) and Perry Hayden (L). (Photo by Wallace Kirkland//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Comparing the diets that concern the longevity of the singular, individual human life and those that are the most sustainable for the planet to then feed entire populations is also an interesting way to see the ways in which humans value their longevity of life, and their own duty as far as determining such a lifestyle to promote immortality in others. Personal anecdotes of foods and other consumables that carried human lives into a second century include carrots, fish, chocolate, cigarettes, port, garlic, and cod liver oil. Other more scientific reports suggest foods high in antioxidants such as blueberries and red beans.

But perhaps looking at communities that show patterns of longer lifetimes is a better indicator of what foods really work best to keep the human body alive. Areas such as Okinawa, Japan and Sardinia, Italy both have desirable traits; Okinawans are the most likely to live the longest, and Sardinian men are most likely to reach 100 years of age. These areas, of course, do not focus on consuming one food considerably more than others to live longer, but instead focus on building patterns of holistic, healthy eating that, with healthier social practices, work together to promote on average ten more years of life than their nearby counterparts.

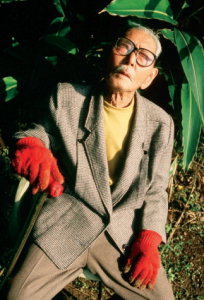

An Okinawan senior taking a break from gardening. Source: National Geographic, 2004

Okinawans have notably high life expectancies (77 years for men, 85 for women), that also include incredibly high rates of disability-free lives, as well as one sixth the amount of cardiovascular disease that the United States does. Their diets are plant-based and have been for centuries. Meat eating was promoted as a rare, social occasion, where every person in the community would then receive a very small portion. The personal involvement of an Okinawan in creating and selecting their diet was then much more personal, as many of the century-plus old Okinawans are constantly gardening and farming their own meals as they have all their lives, often as a result of famine as a result of the United States’ actions in World War II.

In contrast, in a much more distant farm-to-table culture, the economic impact of cardiovascular disease on the U.S. health care system continues to grow, as the cost of heart disease and stroke in the United States is well-known in the medical community to exceed one billion dollars a day, including health care expenditures and lost productivity from death and disability. According to National Geographic’s Dan Buettner, “A rough estimate would suggest that America would save about $300 billion annually if we could bring our heart disease rates down to theirs” in 2004, but with rising numbers it is safe to say that the impact would be much larger.

Imagining the attitudes that would shift toward livelihood, the afterlife, or immortality in an area that could be so starkly different, freed of the economic, social, and cultural burdens, using resources toward providing other means of developing better, longer lives is quite daunting. Perhaps the social indicators of these areas may also point to practices that may be easier for direct implementation into the American lifestyle through promoting social trends and community-building through expansive new social technologies. Okinawans, for example, are well known for their extensive care of elders, promoting sociality, which has been shown to directly promote longevity of life.

Increasing health education as well as the daily interaction with more intimate and accessible food sources would, naturally, aid in creating well-knit communities as well as spread awareness for how to prevent long term consequences of poor health. But lacks of connection to one’s own environment promoted by the growth of human populations and the food industries that exploit them do a good job of actively preventing important developments.

Upon a recent visit to my hometown in Kentucky, I remembered my public high school’s bizarre, unreasonably expensive rejection of the federal lunch program, which was an event popularized to be directly against Michelle Obama’s policies. This demonstrates just one consequence of the growth of the American food industry’s negative influence on countless diets and bodies, and a disconnection with the concept of food being a resource connected to sustainability. The school’s short term gain in 2015 of over $1,000,000 in profits from leaving the federal lunch program do not necessarily promote the long term wellness of students, especially with the district’s consolidation of guidance and counseling services as well as a dramatic staff reduction in 2016, whose announcements were also done in tandem with patterns of obvious political influences after the election of governor Matt Bevin. As Kentucky is 48th in the country in overall health and lifespan, it is obvious that great societal change is needed, but that its immediacy is unlikely.

Sources:

Buettner, Dan. “Who’s Best at Living Longest: The Secrets of Longevity.” National Geographic (2004): n. pag.

Rupp, Rebecca. “The Search for Immortality in Food.” The Plate. N.p., 28 Oct. 2014. Web. 21 Feb. 2017.

Recent Comments