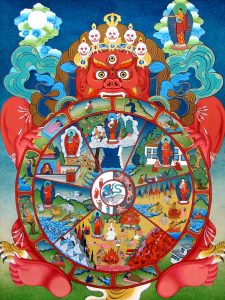

Bhavacakra, or srid pa’i ‘khor lo in Tibetan– also known as the wheel of life or the wheel of becoming– is a symbolic representation of saṃsāra, or cyclical existence, in Tibetan Buddhism. It is believed that the Buddha himself created the wheel in order to explain his teachings. Divided into various sections, the different parts of the wheel essentially denote three different realms of effects of karmic actions.

YAMA:

The wheel is always depicted in Tibetan Buddhist art as being held by the jaws, hands and feet of Yama– the judge of the dead– who turns it, and who represents impermanence. The three layers of the wheel are identified as such:

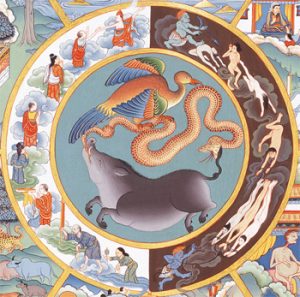

THE CENTER:

The center of the wheel features the three poisons of ignorance (moha)– represented by a pig, attachment (rāga)– represented by a bird, and aversion (dveṣa)– represented by a snake. Tibetan Buddhists consider karma to be created by beings under the influence of these three poisons.

THE SECOND LAYER:

The second layer around the center of the wheel represents karma. The left half is often white, and it depicts people ascending to higher states– an experience obtained as a result of positive actions. The right half is often dark, and depicts people descending to lower states– an experience obtained as a result of negative actions.

THE THIRD LAYER:

The third layer represents the six forms of unenlightened existence, or the six realms of saṃsāra– illustrating the process of cycling through one rebirth after another. This section of the wheel is divided as such:

The Upper Realms:

- Deva – the realm of the gods (heaven) – they are blissful and live enjoyable lives, but pursue meaningless distraction, and are unprepared for death, thus exhausting their good karma.

- Asura – the realm of the demi-gods – they are lesser deities who often fight amongst themselves, or against the more powerful gods. They are characterized as envious and greedy.

- Manuṣya – the realm of human beings – this realm is considered most suitable for practicing dharma, as humans are not completely distracted by pleasure. They suffer from hunger, thirst, heat and cold, as well as not getting what they want, and getting what they do not want.

The Lower Realms:

- Tiryagyoni – realm of animals – they are less intellectually advanced than humans, have little freedom, are driven by instinct and often live in constant fear.

- Preta – realm of the hungry ghosts – they suffer from extreme hunger and thirst, and are depicted with long, thin necks and large bellies.

- Naraka – realm of hell beings (hell) – they are consumed with rage, and undergo torture and suffering. However, they can escape this realm through good deeds and reincarnation.

THE OUTER RIM:

The fourth layer, or the outer rim, is divided into twelve sections– each illustrating in detail the processes in which the three poisons lead to karma, and consequently how karma leads to the six realms of suffering. The twelve links are considered to operate either over several lifetimes, or in every moment of existence. The twelve sections are ordered as such:

1. Avidyā – lack of knowledge, 2. Saṃskāra – volitional action, 3. Vijñana – consciousness, 4. Nāmarūpa – name and form, 5. Ṣaḍāyatana – the six sensory organs, 6. Sparśa – or contact, 7. Vedāna – pain, 8. Tṛṣṇa – thirst/desire, 9. Upādāna – grasping, 10. Bhava – becoming/existence, 11. Jāti – birth, and 12. Jarāmaraṇa – death/decay.

THE MOON:

Above the wheel is often depicted a moon, which symbolizes liberation from cyclical existence. Thubten Chodron, a notable American Tibetan Buddhist, states that, “The moon is nirvana [i.e. liberation]. Nirvana is the cessation of all the unsatisfactory experiences and their causes in such a way that they can no longer occur again. It’s the removal, the final absence, the cessation of those things, their non-arising. The Buddha is pointing us to that.”

A unifying view across all sects of Buddhism is that the cycle of reincarnation can be avoided by reaching Nirvana, which can be translated as “extinction,” or “bliss.” However, if one is not able to achieve this, they are subjected to living over and over again, manifested as something different each time depending on how they behaved in their life before.

The process of saṃsāra, which in Sankskrit means “wandering,” is one of reincarnation and karmic cycle, and thus can be interpreted as a process of immortality. By achieving Nirvana, one puts an end to their suffering and no longer is condemned to repeat this process.

Sources:

“Bhavacakra.” Bhavacakra. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Mar. 2017.

“Buddhist Views of the Afterlife.” Immortality Project. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Mar. 2017.

Recent Comments