“This place is a message…and part of a system of messages…pay attention to it!

Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

This place is not a place of honor…no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here…nothing valued is here.”

-from the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico

Nuclear weapons and nuclear energy have caused us to think differently about ourselves and the possibility of an apocalypse. 72 years on from the Trinity Tests conducted under Robert Oppenheimer, there is still a portion of desert that has extremely high levels of radiation. Other events since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that have shaped our collective understanding of the hazards of nuclear technology include the meltdown at Chernobyl and the earthquake at Fukushima. ICBMs, radiation, and nuclear waste are prominent images within what Jacques Derrida called the “fabulous textuality” of nuclear society in 1984. According to him, all culture since 1945, from his favored field of literature, to science and politics and architecture, necessarily belongs to this Nuclear Epoch.

Apocalypse before the atom bomb was largely the province of religion. Oppenheimer is notorious for his recollection of the Bhagavad Gita while he witnessed the successful test of the bomb, quoting a line from the god Vishnu. That the official start of the Anthropocene was in 1945, however, is not an uncommon argument. Previously, the concept of a secular end of days was fictional in nature, theorized by prescient authors such as H.G. Wells, who imagined the existence of nuclear weapons three decades before they were developed.

At last, humanity’s utter destruction seems to be within our own grasp. There are thousands of nuclear weapons in the world today- even more in the past, before arms reduction agreements and the sluggish administration of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. What I’m concerned with here, however, is actually nuclear energy. It is the processes of nuclear energy production, and not the non-event of a universally destructive atomic exchange, that is shaping the material world and our future at this very moment.

Nuclear energy production is increasing, and will likely continue to increase. This is not recognized as such an immediate danger as nuclear war, but it has its own demands and its own perceived instrumentality, similar to the bombs. Nuclear energy produces deadly refuse, and us mortals are not entirely sure how to handle this. The matter that results from enrichment continues to radiate energy and poses a danger to biological life for thousands of years. Scientists have determined that 10,000 years is a conservative estimate for most of it, while some waste may continue to radiate for up to a million years. In other words, every time we process plutonium for energy, we are creating new radioactive matter that will remain active longer than any empire, longer than written language has existed.

In the United States, 2,000 metric tons of nuclear waste are produced every years. For the most part, power plants keep their nuclear waste on-site. They have nowhere to safely recycle it. In 1982, the federal government passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, which designated Yucca Mountain in Nevada as a planned permanent site of nuclear waste disposal. Since then, it has collected fees from atomic plants to build a massive, deeply-set vault in this area. It has also attracted criticism for its proximity to fault lines and water sources. In 2010, it was sidelined under the Obama administration.

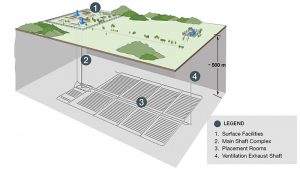

A court order in 2013 canceled the Yucca Mountain plan on the grounds that collecting money for a structure that didn’t even exist was unacceptable over the span of several decades. Its failure was logistical and political, a story particular to the zone itself. There are other deep geological repositories, as they are called, either under construction or being planned. The only such site that actually contains nuclear waste is the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico, and this is an institution that I suggest everyone look into if they’re curious. At the WIPP, the staff is concerned with storing nuclear waste safely, and aims for a 10,000 year structure that can house it. But it turns into a space for philosophical, ethical, and- might I say- existential debate, as well. Allow me to get into it briefly.

Because of the incomprehensible duration of radioactivity with the waste we produce, an entire field of nuclear semiotics has emerged to determine how best to communicate the purpose and hazard of deep geological repositories and other nuclear energy sites. In only 5,000 years it is entirely possible that people will speak different languages. The internet and international political organizations may disappear, and everything from our labor to our systems of knowledge might be unrecognizable. We know that society and culture change quickly. The field of nuclear semiotics acknowledges this, and uses the WIPP as a model for exploring universally effective imagery in language, imagery, and architecture. Embedded within the field are questions of responsibility, ethics, and faith.

Whether or not nuclear waste will even be a main concern thousands of years from now is not clear. “We can never know if we indeed have successfully communicated with our descendants 400 generations removed, but we can, in any case, perhaps convey an important message to ourselves,” said Woodruff Sullivan, a lead research on the WIPP team. The team is composed of scientists and engineers, but also anthropologists, linguists, and historians. Deep geological repositories are pushed by nuclear advocates as part of the ultimate solution to energy shortages, and others recognize them as dangerous for our descendents in the long run.

Thought within nuclear semiotics varies wildly, and it’s worth checking out some of the plans for design at the WIPP and scientists’ theories on earthly society in the far future. Images and architecture are favored, though messages of warning are also currently displayed in the six languages of the United Nations and Navajo. If you’re interested in designing menacing geometries or images that would transcend culture and language, the team isn’t planning to submit a final proposal to the federal government until 2028. Ideas include massive spikes that jut out from the ground, which indicate bodily harm, or massive black slabs that might frighten visitors off. Some other proposals call for the creation of an atomic priesthood and the conscious practice of mythmaking, while another suggests we start breeding cats that can change color when they are exposed to high levels of radiation.

Most interesting is how nuclear semiotics reflect our attempts to understand ourselves. And at times, the experts hired to do the work simply have these whacky ideas. This work acknowledges human mortality and aims to communicate through time. On one hand we are speaking to our greatness with such constructs. In this sense the WIPP and the Yucca Mountain plan are not so different from the Great Pyramids, in that their purpose is to last and to serve as a reminder to subsequent generations of people. The aesthetic and communicative aspects of geological repositories, as they will likely proliferate, are based on different speculations.

We may see waste sites turn into anti-monuments, well-known yet ancient installations of barbarous nuclear material, in a utopian and technically advanced future- where only a particular type of academic can understand the language, as with cuneiform or hieroglyphics today. Maybe they will be seen as cursed, the graveyards of a long-dead breed of magical sinners, because of the harsh architecture and the tendency for those who approach them to come back sick. Is nuclear waste such a huge threat? To me, nuclear weapons pose a more serious danger to human life. Nuclear waste is not a joke, and if we are to produce it, it should be disposed of responsibly. But I think that nuclear semiotics is as often a study in fiction, self evaluation, and philosophical analysis as it is in the protection of future lives. Nuclear semiotics seek to immortalize the anxiety that we feel today about nuclear waste and nuclear weapons, and come from a humanistic, ethical place.

Recent Comments