Group 5 Observations (Alexa, Sabina, Afnan)

Sabina:

Working with the planaria was an opportunity to discuss different forms of immortality and survival. For our group, we noticed that both our uncut worm and a cut piece of tail not only grew, but eventually split apart and regenerated. This splitting was most likely due to depleted resources; the planaria will naturally split when the environment is not proving to be sustainable. However, the reasoning behind this dividing is less clear.

Afnan:

Going into the lab and working with Planaria was not what I expected, I wasn’t sure what to expect. Regenerative worms, specifically worms that can regenerate a whole other head is pretty amazing. As someone who is not necessarily squeamish arounds worms/insects etc working with actual organisms was something I was looking forward to, but when faced with the actual cutting device slicing the tiny worm I hesitated for a second; what if the head didn’t grow back and the worm just dies in a petri dish?

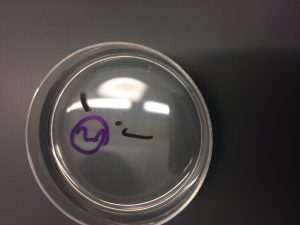

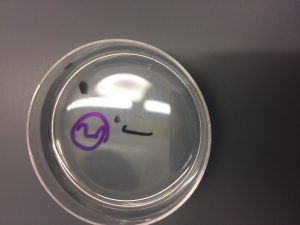

That was obviously not the case considering it split into two. What was a dark clumpy spot after the head was cut, became a light colored still growing head. The second worm, was just a tail still growing but when prodded had a reaction. Apparently this was something Planeria could do, splitting with lack of resources because it also occurred in our third petri dish where nothing was done to the organism at all. But did this worm split off before or after the head re-generated?

The second dish where we had just cut off the tail, re-grew its body but was not as sensitive to light as it was initially. But how often did the organisms need to be feed in order for them to re-generate completely? I assume that if fed regularly they would have re-generated completely with full functions. The organism itself however, is fascinating, and what would it mean if humans could function this way.

Alexa:

I was rather stunned by the results of our Planaria experimentation. I had expected that the first subject (where the head was removed and the body was left in the dish) would regrow its head, because that’s what we had been told. I was unsure if it would have noticeable marks from its decapitation, like a scar along the neck, discoloration of the regrown appendage, or a lack of features such as the light receptors. However the results we saw as well as those of the class at large were far beyond any expectations I had. I was most surprised to learn that no matter what piece of the Planaria was cut off, a new organism would grow back to replace everything that had been lost. It could have been the smallest section of head, middle or tail, and this was something that really impressed me.

In my particular groups results I was most interested in the third Planaria that we left alone which, likely due to the lack of nutrients, naturally and asexually reproduced itself. This was interesting to me because it doesn’t seem like the best solution for a Planaria to duplicate when there is a lack of sustenance. If there is less food wouldn’t more organisms vying for that same food be something the species would naturally want to avoid? I was also curious about the aging of the younger, newly created Planaria. We were told that they do age and eventually die, so does this new Planaria have an extended lifespan compared to what we can call its parent, or does it emerge from the old Planaria already matching the age of the original?

These questions could rationalize the reaction that the Planaria have when put under stressful situations. If the new Planaria is actually a younger Planaria than it’s longer life span does give a slight chance of lasting long enough to survive the race, or at least of reproducing to create another youth and so on.

Images

Recent Comments