The concept of immortality is often thought of in regards to legacy: a byproduct of the self that transcends an individual lifetime.

There is so often a drive to put something meaningful into the world that can both represent who we are and extend beyond the time we spend consciously and bodily on the earth. However, what does it mean when the physical body becomes this legacy, when we ask for our bones to be seen as artwork rather than remains?

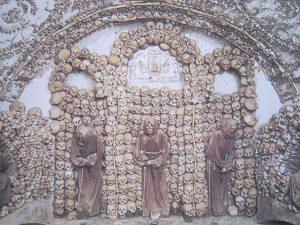

The “Catacombe dei Cappuccini” in Sicily are just that: architecture created from human skeletal remains gathered from Palermo’s Capuchin monks. When the Palermo graves became overpopulated in the 16th century, monks began to excavate crypts and preserve bodies in artistic, nontraditional styles. Being entombed in the catacombs became a status symbol for local luminaries, who would pay pre-mortem to be displayed in a particular fashion. Today, new members are no longer accepted, but the catacombs are open to the public for a mere 3€.

The Capuchin Catacombs have intrigued me particularly because they bring up questions as to what constitutes the individual and the biological lifetime. The Catacombs are a hauntingly beautiful example of biological artwork, a form of artistic expression that intersects with biological elements. Biological materials have been used in the creation of art for centuries, though the field of BioArt has only recently emerged. Works of BioArt prompt viewers to reflect on the capacities of the human, as well as the temporality of life and death.

It is in this sense that the Capuchin Catacombs can inspire us to think about what it means to be a biologically living organism, and how far our physical bodies can be pushed until they are no longer bodies or people: Do our bones stop being ‘people’ after a certain point post-mortem? How long do we have to decay before our bones are no longer part of us?

Even looking at photos of the Catacombs, it can be easy to forget that these intricate murals are composed of remains that were part of living people. Perhaps it happens because not all of the bodies are mummified, but are rather taken apart and repurposed. Maybe this untwining of the whole and tangible body plays a part in why we readily view the Catacombs as museums of artistic expression, rather than just a burial site of the dead.

Biological materials are inexorably woven together with history, whether or not those who come across them know that history.

If given the opportunity, would we choose to have our bones displayed in such a manner – is having your body sought out and viewed by strangers every day the best preservation of the self? To be immortalized – not just through art, but as the art – is an alluring idea.

Recent Comments