The ancient Egyptians believed that a person’s death indicated their departure to the next world. The soul would leave the body, if only for a short time. Death was a temporary interruption of living, and soon the soul would reunite with the body. This is why preservation or “mummification” were so central to the burial practices of the ancient Egyptians. The culture of death and afterlife were dynamic in Egypt, with particular beliefs and rituals changing over time and adapted to specific regions. The earliest mummies were buried out in the dry desert, just under the dunes. The sand would dry out the body and allow for its preservation. Practices became more sophisticated over time, to the point that elaborate mausoleums, and of course the pyramids, were constructed for mummies that ranged from priests and aristocrats to farmers. Even the workers who coordinated the construction of the Great Pyramids had their own burial spaces. Proper preservation involved removing, drying, and storing the organs, draining the body of fluids, stuffing the body with sawdust, and lining the veins with salt.

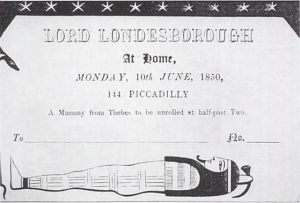

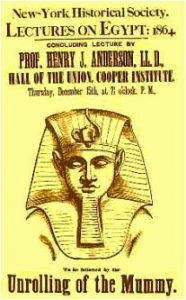

Fascination with Egypt has a long history in European society and predates Howard Carter’s discovery of King Tut by centuries. But English and French imperialism into the country, in relation to the development of modern social and physical sciences, swept Victorian England up in a revitalized Egypt craze in the early 19th century. As a symptom of these historical forces and the gaily Gothic culture of Victorian England, the mummy became a great and enduring icon in the 19th century. In the early days of archaeology, mummies were unearthed and sold; they could be used to make paint or ink, or burned for fuel. Their tombs were raided for jewels and souvenirs, and little attention was given to the ethics of defiling these pre-Christian corpses. But the preservation of bodies from thousands of years ago was no doubt fascinating to the academic and economic elite, as one feature of “Egyptomania” were bizarrely popular mummy unraveling parties. At these events, elite Victorians would gather- sometimes in the hundreds- to drink gin and hold their noses as a mummy from Egypt was uncovered. They were often extremely performative, advertised as an intellectual and exotic spectacle, and often they promised souvenirs of small trinkets or jewels.

The surgeon Thomas Pettigrew was a famous proprietor of mummies at social events, and used them as a foil for his work on racial anatomy. In this regard, Pettigrew was a real piece of work. He wanted to use mummies to make sense of the success of ancient Egyptians in his ethnocentric worldview. He argued that the Pyramids and the rich culture of Ancient Egypt was not possible if the Egyptians were Africans, but instead, the Egyptians were likely Aryan or Middle Eastern, more genetically related to white people than black people. At these events, bodies were removed from their coffins, stripped of their shrouds, and unraveled slowly, methodically, as if consciously fetishized. The hosts would pass ankhs and body parts out among the guests! Not all of them were organized by anthropologists or in anatomical environments, but sometimes they were purely social and without and pretext of imperial academics. The supremely rich might import mummies and have a small group of friends over for a very weird night. Pettigrew was the founding treasurer of the British Archaeological Society, and as I find myself reading about him, it’s clear that hosting these morbid bangers made him immortal in his own way.

The ancient Egyptians believed in immortality as long as they were able to keep their vessels intact. To the early 19th century European intellectual’s mind, this was an absurdity, though reactions to this varied and changed over time. Eventually archaeologists started to argue for preserving these corpses as much as possible, while retaining the ability to study them. But mummy unwrapping parties went on for a long time; the last known gathering was in Manchester in 1908, where an Egyptian baby was unwrapped. They did start to fall out of style around the same time that Egyptian imagery began to enter into literature and fiction. In fiction, mummies took on the Gothic features of their time, as seen in Bram Stoker’s rendition, or they were characterized by an ineffable and alien horror in the work of H.P. Lovecraft. Today they are a popular inspiration for Halloween costumes, with little attention paid to the Egyptian notion of death and immortality or the colonial roots of the mummy’s place within our imagination.

These unraveling events are symptomatic of the concurrent assertions of imperial power and epistemological power, which we can refer to here as secularization. It’s sort of a reverse funeral for a long dead individual that becomes a sacrilegious celebration of white supremacy. As modern people, these bodies do not matter to us- they are objects of study, or stage props, even appropriate for home decoration. They lived long enough ago that we have no tangible relationship to these people. They have not achieved immortality because it doesn’t exist as the ancient Egyptians imagined it, and so there was no impetus to question the morality of these gatherings, particularly because they were not Christians or otherwise enlightened, as we began to imagine ourselves even before the 19th century.

At some point, the mummy became an iconic monster. It may be that unraveling parties played a part in the development of this image. If the unwrapping is a scientific or a social feature of the secularization of death and burial, it is horror at our own society’s instrumentalist perversion that maybe precipitated popular European conceptions of the vindictive, restless mummy guarding his tomb. Thinking of the zombie’s roots in Haitian slavery, I would suggest that monsters are often produced in our collective imaginations through social and political circumstances. I think it is fair to say that these parties are significant because of their being popular in a certain place and time- among aristocrats, intellectuals, the elite of an imperial power, at a time when new forms of knowledge were being organized, and new modes of social organization were emerging. But what is the Egyptian mummy in fiction? What does it tell us about our fears, our hesitations, our regrets?

Recent Comments