The origin of monomyth archetype, or the hero’s journey, can be attributed to American mythologist and writer Joseph Campbell. In his novel The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), he discusses this notion: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man” (Campbell, 23). The hero’s journey is often associated with notions of descent, which abound in world mythology. Various stories tell of quests for self discovery by way of an often perilous journey. This quest has come to be a common theme in comparative mythological studies, and it is usually paired with the notion of confronting one’s own psychological “shadow.”

Katabasis— from the Ancient Greek κατὰ “down” and βαίνω “go”– is a mytheme, which often denotes a hero’s descent into the underworld, “into the cave of initiation and secret knowledge.” When a hero makes the journey to the land of the dead, they are essentially traveling deeper into their psyche in order to confront the shadow. Once the hero has returned from the journey, they have often obtained greater knowledge and are more self-aware. Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist Carl G. Jung invented the concept of the shadow, which refers to an unconscious aspect of the personality with which the conscious ego does not identify itself. He stated that “behind consciousness there lies not the absolute void but the unconscious psyche, which affects consciousness from behind and from inside, just as much as the outer world affects it from in front and from outside.” The shadow is usually associated with the negative aspects of the personality, as those are often concealed.

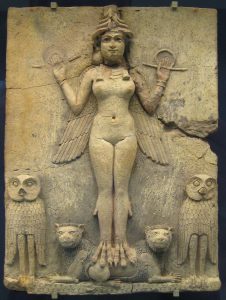

The Ancient Mesopotamian poem, The Descent of Inanna, tells of the interaction between Inanna– the Sumerian goddess of love, fertility and war– and her sister Ereshkigal– the queen of the underworld, and widow to Gugalanna, the Bull of Heaven. The story perfectly exemplifies the hero’s journey by way of katabasis, in that Inanna ventures deep into the underworld so that she can pay her respects to her sister Ereshkigal, for she is essentially responsible for the death of her husband. Ereshkigal, moved by anger and grief at her sister, degrades Inanna by forcing her to remove her garments and bow her head low, and then murders her and hangs her body up as a trophy. Inanna’s descent correlates with the Jungian view of confronting the shadow, as her journey into the underworld represents a journey into her deep unconscious. Only after she has endured not only the torturous underworld, but also the world of her inner darker personality, is Inanna reborn and fully self-aware.

Book XI of The Ancient Greek epic, The Odyssey, tells of Odysseus’ descent into the underworld in pursuit of his nostos, or homecoming. After spending some time on the island of the witch Circe, he is advised to travel to the underworld and consult the blind prophet Tiresias. Odysseus learns that though he may succeed in slaughtering all of the suitors of Ithaca who currently inhabit his house in order to win his wife, Penelope’s, hand, the only way for him to truly obtain his nostos is by embarking on another journey soon after. The sea god Poseidon has condemned Odysseus to a ten year-long journey across the Mediterranean, and in order to make amends, he must venture off to someplace else, and make a ritual sacrifice the deity. Odysseus’ katabasis can be interpreted as a journey into the deeper recesses of his mind, where he will confront his shadow, and upon emerging from deep within his unconscious, he will have obtained a greater understanding of himself, and his objectives in life.

In each account, the hero’s journey is characterized by a descent into the underworld, a confrontation with the shadow and a greater understanding of self as a result. In their decisions to venture to the realm underneath, the two protagonists have essentially given up their lives, but are reborn and emerge anew upon overcoming the darker aspects of their personalities. In this way, the two stories tell of a mode of reincarnation, which can only be achieved through performing an act of katabasis. Jung stresses that in order to gain a better understanding of oneself, it is imperative that a sort of “mental katabasis” be achieved, so that the shadow of a personality may be lessened or exposed.

Works Cited:

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell. Princeton (N. J.): Princeton U Press, 1968. Print.

Young-Eisendrath, Polly, and Terence Dawson. The Cambridge Companion to Jung. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge U Press, 2008. Print.

“Jung’s 1932 Article on Picasso.” Jung’s 1932 Article on Picasso. Web. 15 March 2017.

“Inanna’s Descent: A Sumerian Tale of Injustice.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Web. 15 March 2017.

Homer, and Richmond Lattimore. The Odyssey of Homer. New York: Harper & Row, 1967. Print.

Recent Comments