There seems to be a certain generational divide surrounding technology that becomes evident through nonchalant statements, as well as politicized social works likening social media users to sheep. While this is understandable to a certain extent — this is a completely new form of social interaction– there is a sense of exaggeration and eye-rolling that often comes with discourse around the dangers of technology. However, the changes in understanding of social space is apparent.

A particularly interesting concept within this, and often a rhetoric used to dissuade people from the use of social media, is the everlasting nature of what is posted online. There is a certain immortality to one’s digital footprint, which has subsequently lead to caution and education surrounding interacting on the web. Due to the relative youth of widespread internet access, as well as the appeal of social media to younger people, there is a tendency to assume that online presence is dominated by the healthy or youthful. However, a surprising number of users are also a part of older generations, and thus, the concept of the dead profile is created (along with any other deaths). Over 10,000 Facebook users die daily. There is both a generation born with social media, and a generation dying on it.

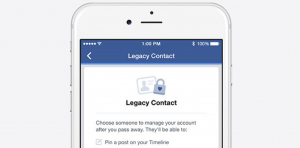

Due to this phenomenon, Facebook has created a memorialization process, and most recently, a legacy feature. Until 2015, after Facebook was notified of a user’s passing, they “memorialized” the account, freezing it as is and not allowing for any further changes. This allowed for a “viewing” of the person, but no interaction. other users were still able to to look through memories and posts on their page, but their social presence retained no further agency. In 2015, Facebook added the “legacy” feature, which allows users to assign a contact to manage their account post-mortem. While this user is unable to read private messages or edit previous posts, they are able to manage any future activity on the user’s page, giving the user a form of social agency after death. This becomes reminiscent of a will, agency being bestowed upon another to continue someone’s social life, and legacy. Users may either choose this “legacy” option, which effectively acts as social immortality through another, or choose termination, which represents their death. So how do people choose? Given the magnitude of social media’s influence in the last decade, this is no small task.

Social media is already a completely new space of social interaction, with very exclusive behaviors and rituals cultivated within the space. The hashtag does not exist outside of its context, and much can be said about other social media born cultural markers, such as memes, follower ratio, finstas, and so on. While these actions may have some root in physical human behavior, they become their own and are dependent upon their respective mediums to exist. Thus, this raises questions regarding immortality within this life. How do we become immortal online, and can this be a stand in for traditional notions of immortality? Further, what concepts of agency does this create, but also invalidate? Creating a “legacy” is a pre-death choice, as well as assigning the person to maintain one’s account. Thus, can further iterations post-death be seen as exercises of the deceased’s agency? Is this disallowing of a social death equivalent to continued life? Does the continued reproduction of memory around the deceased user actually create a space where they are alive, or living a “half life” of sorts? This also brings up the issue of authentic in memorialization. Due to this legacy feature, post death profiles are no longer accurate representations of the deceased, but instead, a curated version of their lived. Therefore, they live on through a crafted persona (although all social media presence is inherently performative). It can be argued that due to the insertion of the 3rd party, regardless of consent, the profile can never be an authentic representation of the user, and therefore cannot be seen as a tool of immortality. The user is stripped of their autonomy regardless of their social continuation. The profiles are are memorials of the user, rather than proxies of them.

In my experiences of the dead on social media, they are spoken of as though they are still with us, comments made on their pages in present tense, and a constant sharing of photos as though that are still alive. How many “#tbt”s does it take to reanimate someone? If their finstas are still alive (run by a close friend or family), aren’t they?

Works Cited

Beres, Damon. “Facebook Just Made It Possible To Will Your Page To Someone When You Die.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 12 Feb. 2015. Web. 03 Apr. 2017

Rowen, Ben. “Facebook User Death, Profile Immortality, and the Issue of Social Media Identity.” Tremr. N.p., 23 July 2015. Web. 03 Apr. 2017.

Recent Comments