R.U.R. is a 1920 science fiction play written by Czech author, Karel Capek. The entire play takes place at the island manufacturing facility of Rossum’s Universal Robots. We are told the story of Old Rossum, who discovered a chemical similar to protoplasm. Rossum set out to create animals, to prove that God was not only no longer necessary in acts of creation — but that God did not exist at all. His nephew, Young Rossum, wanted to use this new chemical to create capital profit. The two split ways, and Young Rossum began to manufacture thousands of Robots.

The story takes place about twenty years later, in the 1950s. The Robots have become crucial to the prosperity of man. They are cheap and plentiful, and are more intelligent and efficient than the average human. Man’s new superfluous status has lead to human births steadily declining; the species slowing going extinct.

However, the creation of a highly intelligent Robot, Radius, spins the danger of human extinction over to human enslavement. While many humans are killed, the Robots take some captive to act as slaves, essentially treating them the same way the Robots were treated in their early days of creation.

R.U.R. ends at an inverse to where it began. As we opened on the creation of the first Robot, we close at the death of the last human. We watch as the Robots develop human feelings and learn to procreate without the assistance of human engineering. Essentially, the world is started over again, with a new species as Adam and Eve.

R.U.R. brings up a discussion of The Uncanny Valley, as well as the emergence of a new classification of cyborgs. It is a piece that asks us to consider the ways in which humanity has been altered by technological advancements, and subsequently reflect on how much we can alter a human until they are something entirely different than part of our species.

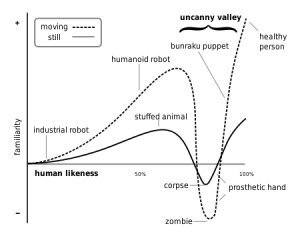

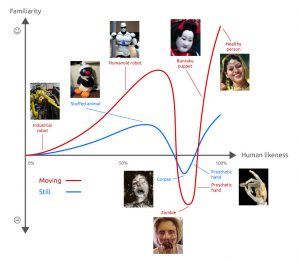

The Uncanny Valley is a term created to reference the phenomenon whereby a computer-generated figure or humanoid robot bearing a near-identical resemblance to a human being arouses a sense of unease or revulsion in the person viewing it. The chart of The Uncanny Valley tracks different objects that arouse certain degrees of “uncanniness” in relation to a living, healthy human.

“Uncanniness” is a type of horror that we experience when things that are familiar to us become horrifically alien (through a change in perspective or circumstance). We like things that resemble humans up to a point. When something becomes too human, but isn’t one (such as a corpse or zombie) we really dislike them. This happens because it provokes that feeling of uncanniness. It can also bring about our mortality salience, the awareness that our death is inevitable. We start to ask: Am I just a machine? Am I alive? What does it mean to be “alive?”

Karel Capek was the first person to ever use the term “robot” in his play. “Robota” is Czech for forced labor, which is literally demonstrated in the humans’ use of Robots for tedious everyday jobs. In R.U.R., Rossum’s robots are made out of fleshy plastic, making them more like cyborgs than machines.

A cyborg has long been a fictional or hypothetical being whose abilities are greater than those of a regular human. The distinguishing feature is that of technical modification, which are built into/built to work with the cyborg’s body to create an enhanced individual. Cyborgs spark particular interest because, in our technologically advanced world, technology supports us in a plethora of ways that were previously not possible.

At what point do we stop being human and start being cyborgs? There is no certain answer because there is no certain definition for humanity. Are we still human when we use tools (glasses, phones, cars, etc.) to improve what nature gave us?

If we are cyborgs, are we still human? Again, as we can’t define humanity, I don’t think this question can be answered. We would have to consider how adaptable “humanity” is before it becomes something else.

In regards to cyborgs, is any form of humanity then a rebellion against a higher cosmic power? Are humans trying to play god?

Sources

Karel Capek. R.U.R. Dover Publications; Reprint Edition, 2012.

Recent Comments